I often tell myself: it’s not that people don’t appreciate you. They simply don’t know you exist. It is said that an average person meets about 10,000 people in their lifetime. Dunbar’s Number theory claims that the human brain has a limit to the number of stable social relationships it can maintain — around 150 close acquaintances or friends; although a few years ago Stockholm University challenged this. Regardless, we often limit ourselves to a certain number of people, and despite their “quality,” we tend to form attachments and are reluctant to let them go in favor of others.

At the same time, we often feel lonely, struggle to find our “people,” and experience a sense of invisibility. The intensity of this feeling of being “unseen” varies across societies, and it begins forming from early childhood.

Stages of Integration into Society

Our childhood integration into the family system is the first and crucial stage of socialization. If a child does not receive recognition, love, and a sense of “I matter” during this period, it can leave a deep mark.

Research that supports this:

- Attachment Theory: children whose emotional needs were not met tend to feel “invisible” and less valuable. This affects their adult relationships — they may either avoid closeness or, conversely, constantly seek validation of their worth.

- Studies on Childhood Emotional Neglect (CEN): researcher Jonice Webb calls CEN an “invisible trauma.” It leaves no physical marks but creates the impression that your emotions don’t matter. In adulthood, this often manifests as chronic feelings of loneliness and low self-worth.

- Intergenerational Trauma Research: studies show that trauma can be transmitted across generations even at a biological level (through epigenetic changes), so the “cycle” can repeat even on this level.

The second and third “integration attempts”

The second “attempt at integration” is school. The third is society at large. If the first attempt was unsuccessful, it is very likely that the trauma will repeat, and a person will wander through the world with a sense of invisibility, undervaluation, or low self-worth. In my case, all three attempts were unsuccessful. Perhaps that is why I don’t feel much difference when integrating into other countries; or rather, I notice cultural differences — with a higher chance of eventually integrating into society in countries where people are generally more visible. I wrote about these feelings earlier, when I noticed the difference on a micro level upon first arriving in Spain — friendly smiles from strangers, a car that slows well in advance at a pedestrian crossing before you even step onto it.

After the third failed attempt, it becomes painful. It’s hard to discern — is something wrong with you, or with the world? Should you continue reaching out, or “not cast pearls before swine”? Deep down, you are fully aware of your own value — so why don’t others see it? What should you do — open up to the “chosen few” or hide yourself to the very end, out of “I’ll do it my way, just to prove a point”?

It’s Easy to Feel Invisible

It’s easy to feel invisible. We imagine that if we are truly valuable, recognition will come automatically. But most people are absorbed in their own lives; they are not scanning the horizon for us. They don’t notice the effort we put in, the thoughts we nurture, or the love we try to express—unless we make it known. And sometimes we do, but somehow it doesn’t register.

This feeling is especially acute when job hunting. We send hundreds of applications, write cover letters, tailor our resumes — and often get no response. After all that effort, it’s easy to interpret the silence as a reflection of our own insignificance. In reality, it’s simpler: recruiters receive hundreds of applications, often very similar, polished to some “golden standard.” In my experience, the most common reasons for rejection or silence are the inability to see the person behind the paper, or, more mystically, that it simply isn’t the right place for us.

Our value doesn’t disappear just because the world hasn’t recognized it yet. The world isn’t a monolith sitting in judgment over who deserves attention and who doesn’t. It is made up of countless individuals, each of whom may one day be the person who “notices” us. In fact, nothing except a monolith is truly monolithic, and I think this is an important point to remember: everything has a complex structure.

Invisible Geniuses

World history offers countless examples of people who remained “invisible” for years before the world finally heard them.

Vincent van Gogh sold only one painting during his lifetime. The problem wasn’t just Van Gogh himself—it was the context: society simply wasn’t ready to see that kind of art. Could he have done things differently? Theoretically, yes — he could have sought other contexts. I’m not advocating marketing, yet it was marketing that ultimately brought him out of obscurity after his death.

And Emily Dickinson? Why did she publish fewer than ten poems in her lifetime, but became a classic posthumously? Perhaps she was sufficiently visible to herself that she didn’t seek recognition from the outside world.

Timothy Leary

Admit it. You aren’t like them. You’re not even close. You may occasionally dress yourself up as one of them, watch the same mindless television shows as they do, maybe even eat the same fast food sometimes. But it seems that the more you try to fit in, the more you feel like an outsider, watching the “normal people” as they go about their automatic existences. For every time you say club passwords like “Have a nice day” and “Weather’s awful today, eh?”, you yearn inside to say forbidden things like “Tell me something that makes you cry” or “What do you think deja vu is for?”. Face it, you even want to talk to that girl in the elevator. But what if that girl in the elevator (and the balding man who walks past your cubicle at work) are thinking the same thing? Who knows what you might learn from taking a chance on conversation with a stranger? Everyone carries a piece of the puzzle. Nobody comes into your life by mere coincidence. Trust your instincts. Do the unexpected. Find the others…

Timothy Leary

Beyond changing contexts and strategies, beyond working on a sense of self-worth and allowing things to happen in their own time as you take your small steps, there is something more.

Timothy Leary’s Interpersonal Behavior Circle Model

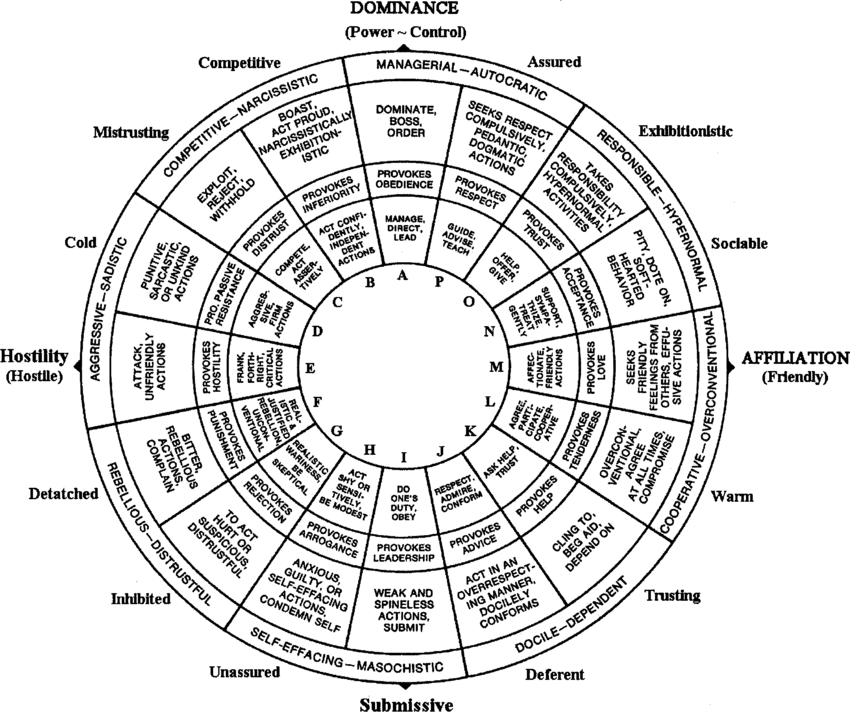

Timothy Leary’s Interpersonal Behavior Circle model maps human behavior along two axes: dominance–submission and warmth–hostility. We often feel unnoticed not because of our own inadequacy, but because our behavioral style doesn’t align with the reactions of those around us. For example, if someone is naturally warm and friendly but encounters indifference or coldness in return, their attempts to connect may go unnoticed. Conversely, if someone is dominant or overly assertive, it may push away those who are shy or cautious.

The principle of complementarity at the core of the model explains how one person’s behavior elicits certain responses from another. Feeling invisible in social or professional environments often doesn’t mean a person lacks value; rather, it indicates that others are not responding “complementarily.” This is particularly noticeable during job searches or in new groups: a mismatch in interaction styles can create the sense of being ignored, even when you demonstrate real value.

Understanding this helps reduce self-blame and pay closer attention to interactions. Leary’s model helps recognize your own tendencies, see how they interact with context, and adjust your behavior to be noticed and heard. Sometimes this means showing a bit more persistence or courage; other times, it means finding or creating spaces where your interaction style is naturally recognized and appreciated. The model shows that invisibility is not always proof of personal deficiency; it can simply be the result of an inappropriate social context that has yet to be found or created.