We use the word “patriarchy” almost automatically, yet rarely pause to ask where it actually came from — because it hasn’t existed always. At no single moment did a man suddenly decide to dominate over a woman, other men, or entire world. Patriarchy is the result of a long, gradual process that unfolded over millennia. It emerged slowly, like erosion: with each generation, women lost a little bit of space, a little bit of autonomy, a little bit of influence — so gradually that the loss itself began to look like the “natural order of things.”

Today, as women regain part of their rights and begin speaking about it openly, many men experience this as an attack on the established world and on themselves personally. It seems to them that women are demanding something excessive, violating the “usual order.” Feminists are often criticised not for their demands themselves but for disrupting an old, convenient “balance.” Their anger and disagreement are perceived as “unfeminine,” aggressive (since anger is culturally monopolised by men and women’s anger is uncomfortable), because a woman is “supposed” to speak only in ways acceptable within patriarchy — restrained and elegant, without threatening established roles or, heaven forbid, a man’s sense of worth.

Misogyny does not appear out of nowhere: it is a reaction of a system accustomed to women’s silence, to women remaining objects of control rather than subjects of their own narrative. At the same time, patriarchy harms men as well: it imposes rigid frames, punishes emotion and vulnerability, and sustains a culture in which violence is treated as normal.

Pre-hierarchical balance

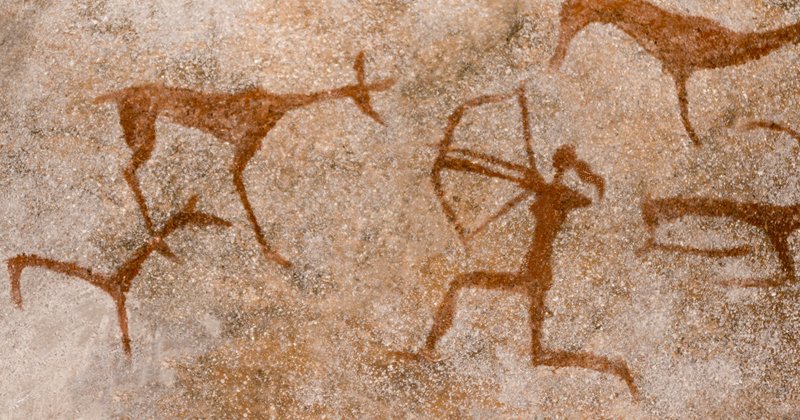

Early human societies did not know patriarchy. In hunter-gatherer groups, no fixed hierarchy between women and men existed. The division of labour was shaped by seasons, personal skills and the needs of the group — not by superiority or inferiority. Archaeological findings, including burials of women with hunting tools, and modern ethnographic studies also show that the “male hunter — female gatherer” model is a late stereotype (The Conversation 2020, Live Science 2023).

Anthropologist Mark Dyble notes that equality may have been one of the traits distinguishing early humans from other primates. “Chimpanzees live in quite aggressive, male-dominated societies with clear hierarchies,” he said. “As a result, they just don’t see enough adults in their lifetime for technologies to be sustained.”(The Guardian 2015). Human communities, by contrast, were more open and flexible, and this mutual dependence facilitated the development of social and technical skills.

In such conditions, all work had equal weight: gathering, hunting, childcare, tool-making — everything sustained the community. The female body was associated with birth, fertility, and life. Many ancient cultures centered around the image of the Great Goddess — a symbol of creation, cyclicality, and abundance.

Strength, war, and “protection”

As material wealth accumulated, conflicts over resources intensified. Warfare made physical strength, discipline, and capacity for violence key criteria for authority. The warrior figure became a symbol of power — and power meant the right to set the rules.

Here emerges the logic of “protecting women,” which quickly transformed into control: in order to “shield” them, women were restricted and isolated, and control over the female body became the foundation of controlling society. Simultaneously, the notion of “male honour” developed, directly tied to the behaviour of women. Her freedom was treated as a threat to his dignity.

The process formed gradually: with each generation, women lost autonomy, space, and influence. Early legal codes — from Sumerian to Babylonian — often equated a woman’s status with that of slaves or livestock. Marriage became a contract between men, and control over women’s bodies became a mechanism for maintaining social order.

Despite this, women always resisted: through escape, sabotage, women’s communities, rituals, and informal networks of mutual support. But history was written by those who had access to literacy and political power — primarily men — so much of this resistance remained invisible.

Religion, philosophy, and science as justification

Religion legitimised patriarchy by constructing the image of woman as the bearer of sin and bodily weakness. Classical philosophy and early science solidified this further: for Pythagoras, the chaotic woman threatened cosmic order; for Aristotle, woman was a “misbegotten man.” In the nineteenth century, medicine, early anthropology, and racial sciences produced pseudoscientific claims — “hysteria,” skull measurements, and ideas about women’s supposed emotional and intellectual inferiority.

Modernity: new faces of an old system

Today, equality is formally declared, yet patriarchy continues to operate through jokes, linguistic stereotypes, ideas about “female logic,” evaluations of leadership, and norms centred on strength. Control over women’s bodies and autonomy remains fundamental. It is sustained by fear of women’s freedom and embodiment: control over reproduction and over cultural memory continues to structure society.

In the painful transition from domination to partnership, we see significant backlashes. In some countries, control has taken radical forms. Afghanistan, where women are stripped of access to education, movement, work, and even public visibility, is only the most obvious example. Similar models exist elsewhere: where political or religious authority is built on fear of female autonomy, women are hidden, isolated, rendered invisible. When a society fears women’s presence, it seeks to return to the harshest version of patriarchy — the kind in which women’s freedom is perceived as a threat to social order itself.

This dynamic is reinforced by the global shift to the political right. Conservative and far-right movements are gaining strength across the world, offering a “return to traditional roles” as a remedy for social change, migration, economic instability and collective anxiety about the future. In such rhetoric, women again become symbols of “morality,” “civic order,” and “national culture,” which must be controlled, restricted, and kept within the bounds of a “proper” life. Under the guise of protecting tradition, patriarchy gains new momentum, and women’s rights once again come under threat.

Personal experience: patriarchy of the brain

Recently I met a man whose personality and creative work genuinely appealed to me. Our conversation was light and effortless until I said the phrase “woman is the source of life.” He literally exploded, shouting that this was nonsense because men and women are equal. The very idea that a woman might be special in any way provoked him so deeply that he shut down completely: the statement about women’s life-giving role felt to him like a threat to his worth as a man. He, of course, did not see it this way.

This episode illustrates a deeper cultural logic: patriarchy restricts not only women but also forces men to define their own worth through comparison with women. Even though we both agreed that men and women are equally valuable, continuing the conversation became impossible — his defensive reaction was too strong.

Men cling to being “better” because patriarchy shapes male identity through comparison and control. In this case, the comparison did not favour the man, and control manifested as refusal to discuss anything unfamiliar or emotionally challenging, accompanied by demonstrative “righteous anger.” A man’s social value under patriarchy is defined not by itself but relative to others — foremost to women.

What we fear

Women’s autonomy in such a system is experienced as a threat because boys are taught from childhood to be strong, unemotional, leaders. Historically, “being better” meant the ability to defend resources, family, and status. In today’s world, this is expressed less as an actual need to dominate and more as a fear of losing one’s role, significance, and control. It is not about “superiority” over women but about vulnerability disguised as competition.

I experience a similar panic when a man tries to restrict my autonomy — for example, by pulling me into a “family” as if this should automatically strip me of freedom, space, and the right to define my own life. In these moments, resistance rises inside me: not because I reject relationships or closeness, but because I sense a threat to my selfhood. My body and experience remember well the historical scenarios in which women were “included” in a family at the cost of their will rather than by choice. My subconscious still sometimes retrieves those “old familiar” patterns — to serve, to smooth everything over, to take responsibility for everyone — but I do not want to continue that logic.

The difference is that my fear is historically grounded, rooted in real generational experience, whereas his fear is shaped by a system that trained him to compare, compete, and fear others’ autonomy. A person tries to sit on two chairs at once — consciously declaring equality while subconsciously unable to let go of the dynamics of domination.

In summary

Patriarchy is a social construct, not a natural order. It can and should be dismantled through education, legislation, culture, and conscious individual action. This is not only a struggle for women’s rights — it is a path toward a healthier, more balanced society in which freedom and responsibility are shared equitably, and violence and control become unnecessary.