Throughout the past two years, I have thought a lot about what time is and how we experience it. During emigration, relationships and their breakdown, adaptation to a new society, moments of sadness, anger, joy, anxiety, and tension, I felt time differently and reflected on it often.

In Alice in Wonderland, time appears as a character: it can stop, take offence, force action. Alice senses that time flows differently in different places and for different characters. An hour can feel long or short depending on the situation: time is not an absolute measure but an experience. Characters who dismiss rules, timekeeping, and punctuality constantly appear in the book (for instance, the White Rabbit, always late). The tea party goes on endlessly — Alice and the Cheshire Cat are stuck in “time that doesn’t move,” or in a cycle without beginning or end: here Lewis Carroll shows that time can be cyclical, perceived only through events rather than clocks. This is very close to Mbiti’s African concept where “events create time.”

This difference in how Europeans and Africans perceive time is precisely what I want to reflect on.

European sense of time: consumerism and authoritarianism

In most European countries, time is perceived as currency. One can “spend,” “save,” “waste,” or “invest” it. From childhood, we are taught punctuality and efficiency. Being ten minutes late feels like failure; a day without productivity turns into guilt. Time is money.

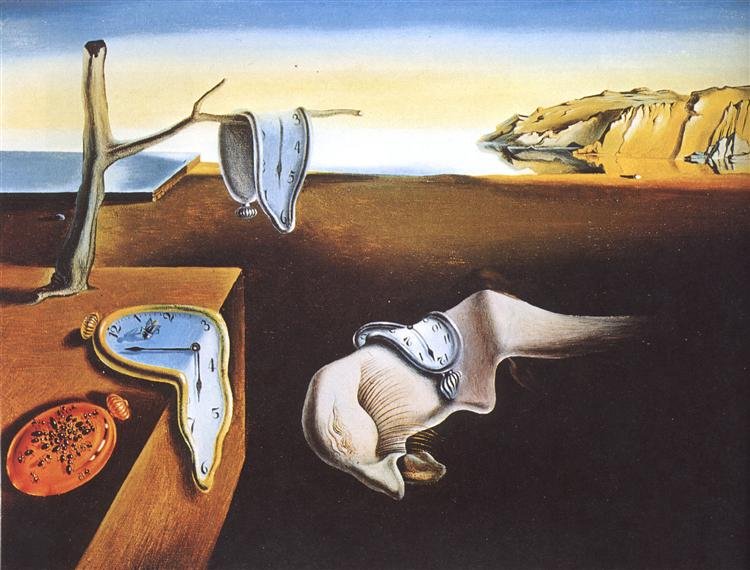

This mindset has taken shape over centuries — through industrialisation, Protestant work ethics, and bureaucratic order. The clock — once a monastic tool for prayer — became the ruler of the modern world. Every train, every meeting, every contract depends on collective obedience to precise time. Efficiency has become a moral category.

Through colonialism, European time became the global standard. Time zones, schedules, bureaucratic calendars — these are tools of control, and we have suddenly become slaves to them. The rhythm of factories and churches became the rhythm of empires. European punctuality was equated with civilisation, while slower, cyclical, or community-based rhythms were seen as primitive. Today Europe looks closely at what it once dismissed as “primitive,” vaguely beginning to recognise its value and its own pallor.

The burden of “you must”: when routine feels like violence

In contemporary Europe, routine often carries emotional strain. It is not merely habit, but a structure of obligation — repeating what must be done. For many, it evokes associations with patriarchal control: invisible pressure to cook, clean, care. Something one longs to escape.

In cultures that value freedom, autonomy, and self-actualisation, “you must” is experienced as violence. Household rhythms clash with the ideal of an independent person. Instead of security, routine brings a sense of captivity — an endless loop of tasks with no recognition and no sense of progress. Clean — and suddenly dirty again.

This strain intensifies in individualistic societies where communities have shrunk into small or nuclear families or solitary households. What was once done together now rests on the shoulders of one or two people who pay dearly for loving personal space. The result is exhaustion, because being independent does not mean being able to do everything. In truth, doing everything is impossible anyway.

Recently, a Dane, Torbjørn C. Pedersen, returned from a ten-year journey: he set himself the goal of visiting every country in the world without flying. One of his conclusions upon returning home — everything is vanity, except relationships with people.

Domestic labour as “lost time”

Within European logic of productivity, household chores are rarely valued. Cooking, cleaning, caregiving — actions that sustain life — are viewed as secondary, as “wasting time.” A perfectly tidy home may be nice, but it doesn’t evoke the respect that a successful career or some impressive achievement does.

Thus, routine is delegated or automated: robot vacuums, food delivery, cleaning services. The idea is clear — time should serve self-realisation, not domestic maintenance. Repetition contradicts the European idea of time as progress — something that must always move forward, linearly, not in circles.

European perfectionism

In Europe, it is important not only to use time efficiently but also to achieve flawless results. The home must shine, the body be toned, the email inbox emptied, the child develop according to plan and attend all activities. I do not meet my own expectations for time and am especially horrified by my impatience beside a child for whom time doesn’t yet exist.

Perfectionism is not aesthetic taste but a moral demand. It is a form of control turned inward. A spotless kitchen becomes a sign of self-discipline: I managed, I control the chaos. But life is by nature messy. A home is not a hospital. Messiness is a sign of life.

Perfectionism turns the home — a place of rest — into a site of anxiety. In the pursuit of flawlessness, there is no space for joy or spontaneity. Disorder becomes yet another reason to feel guilty.

The inner clock: anxiety as a cultural habit

Living by the clock generates a particular form of inner tension. Even in silence, we hear time passing. Constant glances at the clock and anxious self-monitoring — Have I used my day well? Have I done enough? We rarely rest without guilt. We scroll through feeds, multitask, fall asleep thinking about unfinished tasks.

Today the rhythm is dictated not by the clock tower but by the smartphone. Work intrudes into rest; leisure becomes content. Time, once divided into hours, dissolves into seconds of reactions. Digital life has not freed Europeans from the tyranny of time — it has intensified it. We are always connected, always in motion, always a little late. The boundary between “on” and “off” has vanished. In this state of constant readiness, the mind forgets what it means to be here and now.

Another kind of clock: African rhythms

In many African societies, time is perceived as flexible and relational. Life follows natural and social rhythms rather than strict schedules. What matters is not the hour but the moment — whether people are ready, whether the mood is right, whether community needs align. I feel this as a lost value.

The anthropologist John Mbiti wrote that in traditional African thought “time moves backwards”: what is real is the present and the past, while the distant future is insignificant. The value of time lies in the event.

Time is not an abstract line stretching endlessly forward — it consists of events. As Mbiti wrote, events create time. If nothing happens, there is no time. Only what has already been experienced exists: the past (zamani) and the living present (sasa). The distant future imagined by the West does not yet belong to time, because it hasn’t become reality.

Mbiti explained that many East African Bantu languages do not have words for distant future concepts like “next century.” The future is not an empty space to be filled; it is only a shadow until it becomes experience. Thus, time is not cosmic or mechanical but reciprocal, cyclical, communal.

Creating time

In African cosmology, people create as much time as they need through events: seasons, rituals, conversations. A year does not end after 365 days but after four seasons — two dry, two rainy. What matters is not the number of days but the rhythm of life.

This sharply contrasts with the Western idea of time as a commodity — something to spend, save, or waste. When an outsider sees people sitting under a tree and thinks they are “killing time,” they are mistaken: in African understanding, sitting under a tree is not idleness but waiting for time or even creating time. (Borrowed from this wonderful woman)

If Western modernity seeks meaning in the future — in progress, development, endless growth — African thought finds meaning in continuity, in the living presence of ancestors, in cycles of birth, growth, death, and renewal. The golden age lies not ahead but behind — in zamani, where all experience is gathered. In the West, a pause is failure; in African time, a pause is fullness.

Western religions imagine time as movement toward an end — salvation or apocalypse. In African temporality, there is no end: it is eternal renewal. Time is not money but life unfolding in relationships.

Mbiti’s perspective exposes the hidden arrogance in the Western belief that only linear, future-oriented time can be real. He offers another relation to existence — where time is not conquered or optimised but lived and shared.

From forcing to joy: the phenomenon of hygge

Some European cultures have learned to soften the sharpness of time. The Danish concept of hygge is not only about candles and coziness but about a philosophy of making peace with daily life. It turns repetition into ritual and household chores into pleasure. Folding laundry, baking bread, tidying a room become ways to connect with reality through touch, smell, movement. It is the art of enjoying simple things.

Hygge reinterprets domesticity as a space of belonging, including belonging to oneself. It transforms “you must” into “I want”: we cook not for efficiency but to eat or nourish others; we clean not for control but to feel calm. It is a way to reconcile with imperfection — a gentle protest against the morality of time.

A feminist return to routine

More and more women and thinkers are reinterpreting domestic practices not as submission but as strength. They argue that care — for the home, the body, others — can be a form of autonomy when chosen consciously. Cleaning or cooking, in this view, is not regression but resistance: refusing to evaluate oneself solely through productivity.

Returning to one’s own rhythm restores dignity in the everyday. It turns the former “you must” into an act of self-definition, acknowledging: this too is life, and I choose to be present in it.

Recently at university, we wrote an essay about home, and only afterward, after submitting the work, I realised that home is whatever we care for — whether it is a body, a small dwelling, a country, or a planet.

Rituals as rest

Cooking, cleaning, and other simple repetitive actions can be deeply calming if freed from the pressure of results. They give rhythm to a scattered mind, a sense of completeness to tired hands, a space for thought or finally for thoughtlessness.

When time ceases to be a battlefield for efficiency, routine becomes meditation — a dance between body and mind. Household labour is not lost time but a conversation with oneself that restores wholeness. Perhaps nature did not intend these routines in such quantities — we organised our lives in ways that made things harder — but it certainly intended them as a way to ground ourselves.

A more humane time

European obsession with precision, efficiency, and perfection may reflect a deeper fear — of chaos, dependence, mortality. But control often costs us connection. Seeing time as something to use, we forget that we must live in it.

Other cultures remind us: time can be circular, shared, slow. Learning flexibility does not mean rejecting structure, but softening it with compassion. Everything that truly matters cannot be measured or optimised.