People tend to fall into quick-hatred. The anger accumulated in everyday life — at small everyday irritations, at everything that slips beyond our control — seeks an outlet, and the media narrative often offers a target for it. There everything is explained clearly: there is good, there is evil, evil attacks good and must be punished. There cannot be three truths, because that would be too complex for quick-hatred, which simply needs a place to dump its negativity.

Quick-hatred

People go on social media and react with angry emojis under arguments, pouring out fury instead of engaging in discussion. Many of them have never had any personal experience with those they direct their anger at, yet everyone remembers how in 2001 two towers fell picturesquely on television, and an entire “race of terrorists” was instantly declared guilty. People who leave angry reactions and hurl curses often lack the broader experience that would allow them to see the complexity of others. And it’s not interesting anyway — because then where would the anger go?

Kharkiv

When I first arrived in Kharkiv in 2007, I quickly grew to hate it. A terribly russified city with rude people. A hideous, hideous city where I had to live for five months. In 2021 I returned there for the second time and discovered a completely different side of it: a Ukrainian-speaking cultural community, cafés where Russian was forbidden. Happy days of reconstructing the city in my mind and soul. The very same city that I hated all those years ago was the one I later had to mourn sincerely as I watched it crumble into ruins.

Gaza

In the same way, my friend first visited Israel and then Gaza, returning with impressions shaped by stark contrast: progressive, modern Tel Aviv, into which endless resources have been poured, versus Gaza — worn-down, dirty, cut off from the world, with grimy children clinging to tourists.

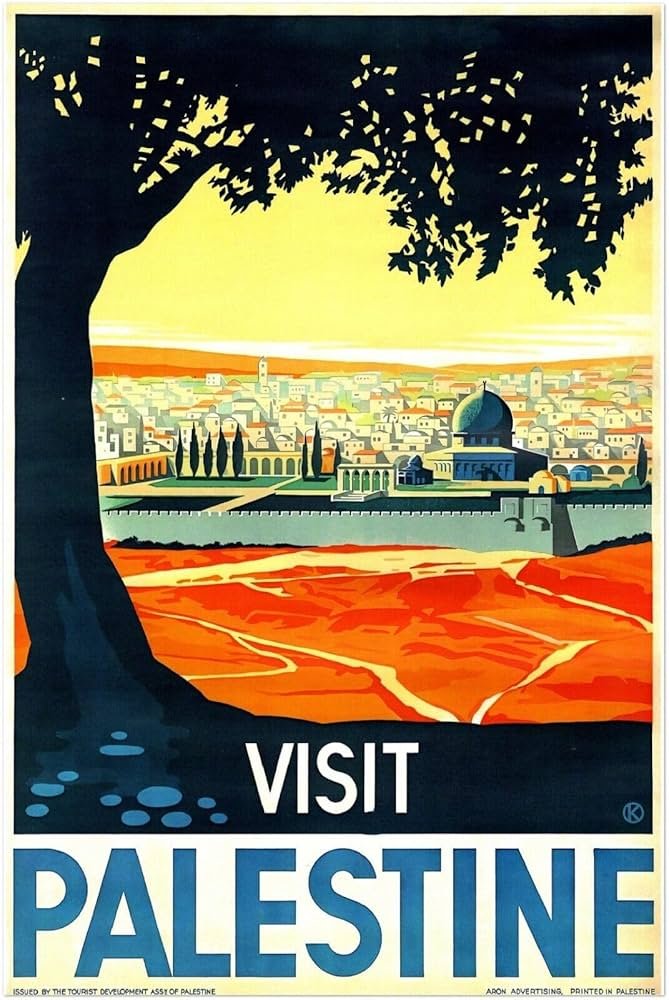

I have never been to Gaza, but I have been to several Arab countries and lived in one of them for six years. I have seen two very different Arab worlds. I have seen the poor and uneducated, and I have seen intellectuals and creators. I have seen exiles from Palestine who found refuge in Lebanon without passports. I have seen passports that list “occupied territories of Palestine” as the place of origin. I have seen people who keep the keys from homes stolen from them in the distant sixties. I have seen Palestinian art, embroidery, pottery, the famous “Visit Palestine” posters lovingly displayed in many families’ homes — symbols of hope that one day it will become reality, and they will be able to welcome guests without a gun pointed at them, without asking permission from an occupier. And most importantly — we shared many meals together.

A nation is not a monolith

I will never stop repeating this: no nation is a monolith. A nation is an artificial political construct stretched over peoples like an owl over a globe. Beneath this word lie very different individuals who nonetheless feel a sense of belonging and have the right to be together and to live on their own land. They have the right to water, food, healthcare, education, and a basic sense of safety. Hating a “nation” is as senseless as hating a race or a gender. Hatred does not protect from harm.

Today we hate Russia, and that is understandable. Somewhere in the back of the mind there is a rational layer whispering that there are exceptions — people who have not been brainwashed, who spoke out against the war, who raised money to support Ukraine. But now, in wartime, we do not have the moral space to look for anything good there. First we must survive, then recover — and the brain cannot even begin to process anything beyond that. We are in survival mode. And yet we coexisted even after a series of Holodomors. Incredible, but true.

But we do not have to blindly divide everything else around us into black and white, applying our own tragic experience to everything. The world consists of many truths and untruths, of narratives told by politicians, and of grassroots stories that, unfortunately, are often absent from textbooks. The world is complex — as is every individual within it. The easiest thing is simply to take a side and fall into quick-hatred, without looking into nuances, without hearing people’s stories.

Shared experience

Recently I learned about the concept of commensality — the shared act of eating and drinking that becomes a positive unifying experience. Even Russians have friends — someone has shared meals with them.

In Liberia, there is a form of resolving social disputes in which all parties and their families gather together, listen to one another, and then the person deemed guilty must treat everyone to food and drink. A shared meal ends the conflict. Similar practices exist in other African countries as well.

Some African tribes have a custom of marrying exclusively across clans. When a dispute arises between them, kinship smooths the sharp edges, and the motivation to resolve the issue increases significantly. International marriages likewise soften conflicts, introduce families and friends to one another, and compel people to stand up for their new loved ones before their old ones and vice versa. International children are something special — they automatically represent both parents’ peoples and mediate between them. Sometimes it seems to me that the world is held together by these small unions, just as royal international marriages once protected states from war.

When we travel, we rarely complain about a lack of hospitality — usually guests are welcomed everywhere, treated like family, offered food, and invited to share stories. After that, there is no room left for hatred. You carry these stories with you, but those who have not heard them or lived them personally are not always ready to make space for another in their heart. Perhaps the solution is to see people before hearing the narratives about them — narratives that inevitably serve someone’s interest. And the anger? It can be directed toward accepting responsibility and making small, daily efforts.